Why VO₂ Max Should Matter to Every Tactical Athlete

From Tactical Performance to Healthy Aging—Why Cardiorespiratory Fitness Matters

Introduction

Tactical athletes face constant uncertainty. At any time, you may need to cover distance under load, generate high force, or make clear decisions under stress—rarely with a predictable schedule. Those same demands, however, help build the pillars of long-term health: a healthy cardiovascular system, strong skeletal muscle, and a sharp brain.

This article begins our deep dive into one of those pillars—the cardiovascular system and endurance performance—starting with VO₂ max. Few measures carry as much weight: VO₂ max is one of the strongest predictors of both performance capacity and long-term survival. It’s not the only factor that matters, but its significance is undeniable. For tactical athletes—and anyone serious about health and performance—VO₂ max is a metric worth understanding and improving.

What is VO₂ Max?

VO₂ max is the maximum amount of oxygen your body can use during intense exercise. Think of oxygen as the fuel for your aerobic system: the better you can take it in (lungs), deliver it (heart and blood vessels), and use it (skeletal muscle), the more work you can sustain before fatigue sets in.

Scientifically, VO₂ max is determined by two factors: how much blood your heart can pump (cardiac output) and how much oxygen your muscles pull from that blood (oxygen extraction). It is usually expressed in milliliters of oxygen per kilogram of body weight per minute (mL/kg/min). In practical terms, this unit simply allows us to compare fitness fairly across different-sized individuals. VO₂ max is calculated using the Fick Equation:

VO₂ max = Cardiac Output (Heart) × Oxygen Extraction (Muscles)

To maximize VO₂ max, your lungs must bring in oxygen, your heart must pump blood efficiently, your blood vessels must transport it effectively, and your muscles must extract and use it well. This is why VO₂ max is so valuable: it reflects how well your heart, lungs, blood vessels, and muscles work together as a single system.

Why VO₂ Max Matters

A higher VO₂ max equates to a larger aerobic engine. The larger your aerobic engine, the more work you can do and the longer you can sustain it. In practical terms, that means:

- Greater capacity for sustained endurance work

- Faster recovery from hard efforts (both within a workout and between sessions)

- Greater resilience to stress (often seen in measures like heart rate variability)

- Sharper decision-making under fatigue

- Reduced long-term health risk

In short, VO₂ max is critical for both health and performance. It raises the ceiling for endurance, accelerates recovery, builds resilience, and supports healthy aging.

Note: VO₂ max isn’t the only factor that matters for endurance performance. Lactate threshold, movement efficiency, and mental resilience matter too. But as a single measure that connects both performance and longevity, VO₂ max stands apart.

Clarifying Terms

In the research world, you’ll often see the terms VO₂ max, cardiorespiratory fitness, and maximal oxygen uptake. These all refer to the same thing: how much oxygen your body can use during hard exercise. If you see any of those terms, think of them as different names for the same concept.

You may also see the term “MET” (metabolic equivalent), which is another way to measure exercise intensity. One MET is the amount of oxygen your body uses while sitting quietly at rest. The higher the METs, the harder the effort. For example, walking briskly might be 3–4 METs, while running hard could be 10–12 METs.

Researchers often use METs instead of VO₂ max because they’re simple to calculate during treadmill or exercise tests, making them an easy and standardized way to compare large groups of people. To connect the two: 1 MET is equal to about 3.5 milliliters of oxygen per kilogram of body weight per minute—the same units used for VO₂ max. That’s why METs serve as a good proxy for VO₂ max in research.

In short:

- VO₂ max = Cardiorespiratory Fitness = Maximal Oxygen Uptake

- METs = Another way of describing exercise intensity

- Peak METs = Highest aerobic effort achieved during testing; a strong proxy for VO₂ max

With those terms clarified, lets look at what the research actually tell us about VO₂ max and survival.

What the Research Says

Across numerous large-scale studies, VO₂ max has consistently emerged as one of the strongest predictors of long-term health and mortality. Simply put, your level of cardiorespiratory fitness is a powerful predictor of how long—and how well—you will live. Here are two landmark studies that highlight this:

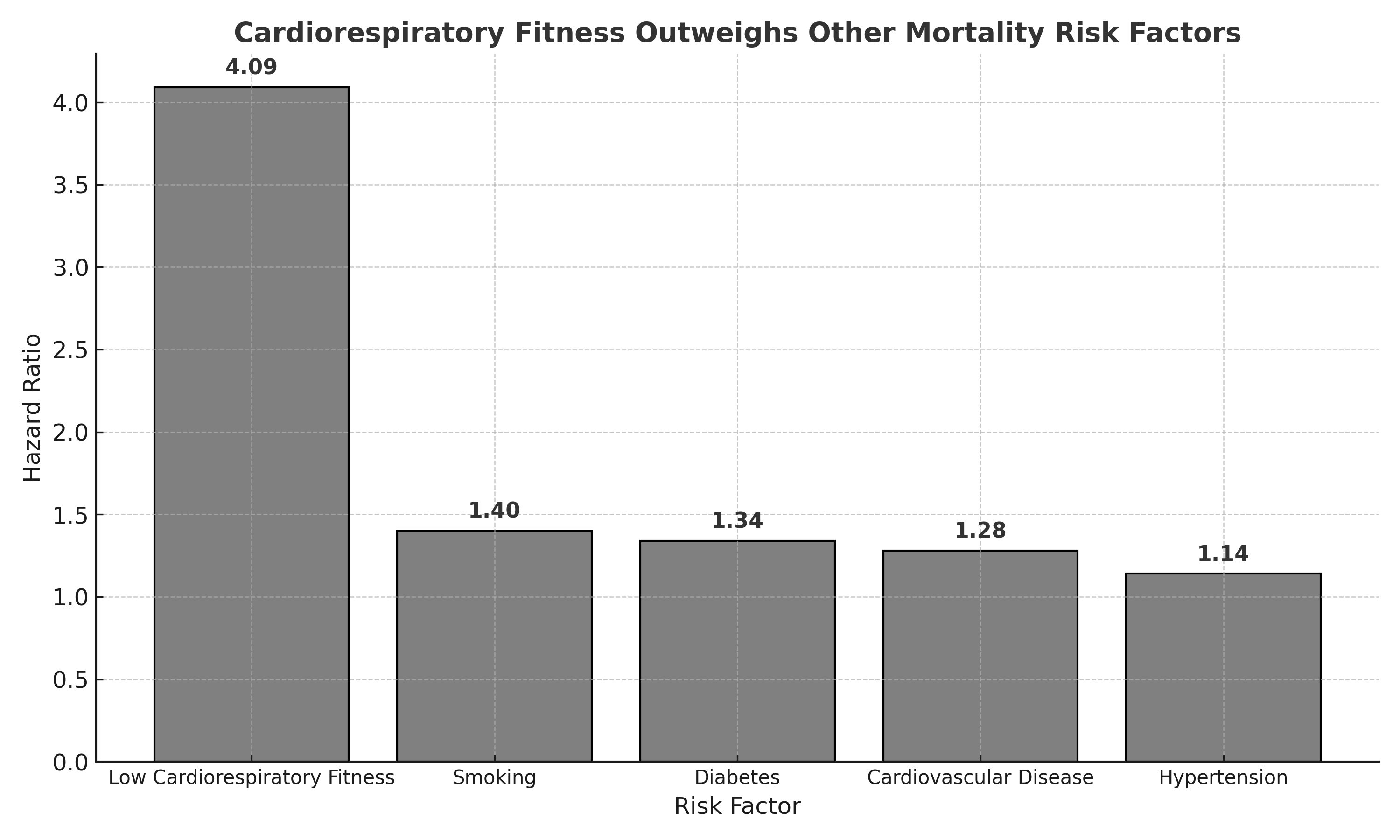

- Cardiorespiratory Fitness Outweighs Other Mortality Risk Factors

A 2022 study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology followed more than 750,000 U.S. veterans to compare the impact of cardiorespiratory fitness against other well-known health risks such as smoking, diabetes, and high blood pressure. Instead of directly measuring VO₂ max, the researchers used peak METs (metabolic equivalents) from treadmill testing to estimate fitness.

The scientists relied on a statistic called a hazard ratio to compare risks. A hazard ratio is a way to compare risk between groups—for example, how much more (or less) likely one group is to die compared to another. In this study, the outcome was death. The fittest individuals (those with the highest cardiorespiratory fitness, top ~2%) served as the reference group, assigned a baseline hazard ratio of 1.0.

Here’s what they found:

- People in the low fitness group (bottom 20th percentile of peak METs) had a hazard ratio of 4.09—meaning they were more than four times as likely to die during the study compared to the fittest individuals.

- By comparison, hazard ratios were much lower for other major risk factors:

- Smoking – 1.40

- Diabetes – 1.34

- Cardiovascular disease – 1.28

- High blood pressure – 1.14

In plain terms: poor cardiorespiratory fitness carried a far greater risk of early death than smoking, diabetes, or high blood pressure. That doesn’t mean those conditions aren’t problematic—they clearly are—but it underscores that cardiorespiratory fitness is more than a performance metric. It’s a survival factor.

Importantly, the researchers adjusted their analysis for other major risks like age, smoking, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. This means the increased death rates in the low fitness group weren’t just explained by disease. Cardiorespiratory fitness itself stood out as a strong, independent predictor of long-term survival—providing protection above and beyond other risk factors.1

While this study was done in a veteran population, its message aligns with decades of research in broader groups: aerobic fitness is consistently one of the most powerful predictors of health and longevity.

Figure 1. Low cardiorespiratory fitness is associated with a greater risk of early death than traditional risk factors, including smoking, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and high blood pressure (Kokkinos et al., 2022).

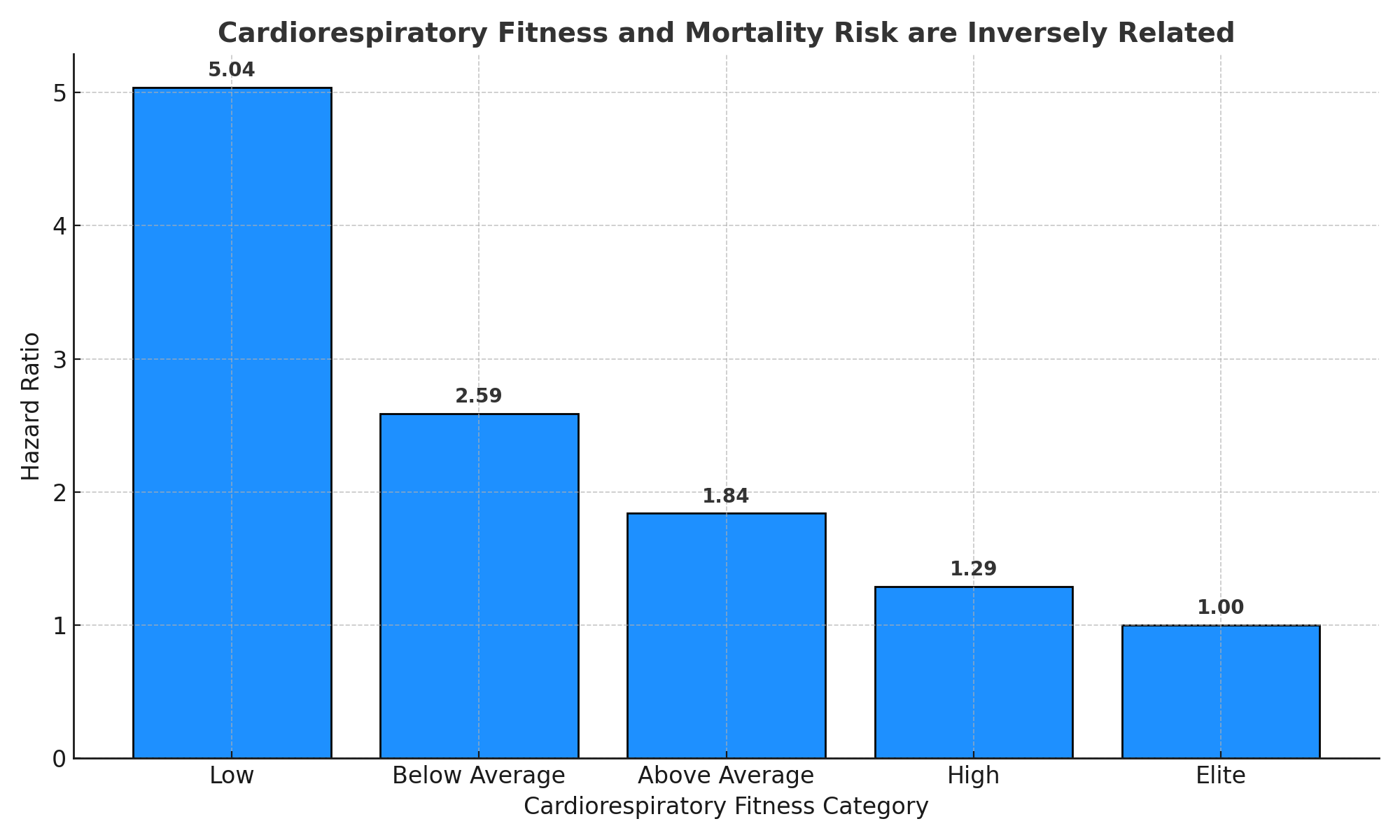

2. Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Mortality Risk are Inversely Related

A 2018 study published in JAMA Network Open followed more than 120,000 adults who completed treadmill exercise tests and were tracked for long-term survival. Participants were grouped into cardiorespiratory fitness categories based on age- and sex-matched percentiles:

- Low: <25th percentile

- Below Average: 25th–49th percentile

- Average: 50th–74th percentile

- High: 75th–97.6th percentile

- Elite: >97.8th percentile

The results were striking: higher cardiorespiratory fitness was strongly tied to longer survival, with no upper limit to the benefit. Those in the lowest fitness category faced more than five times the risk of death compared to the elite group. Put differently: someone with very low fitness was over five times more likely to die during the study period than someone with elite fitness. Yet even a small improvement—from “low” to “below average”—nearly cut that risk in half.

The figure below illustrates this clearly: as fitness rises from low to elite, mortality risk steadily drops, with no point at which the benefit levels off. Unlike other health measures (like blood pressure or cholesterol) where benefits plateau, the protective effect of aerobic fitness showed no ceiling.2

This study highlights two key takeaways:

1. Small Improvements Matter — Even modest increases in fitness substantially lower mortality risk. You don’t have to be elite to gain significant benefits.

2. More Is Probably Better — The protective effect of cardiorespiratory fitness showed no upper limit. If you enjoy pushing your aerobic capacity, your efforts are likely rewarded with continued health benefits.

Important note: While research suggests no upper limit to VO₂ max benefits, the training load required to reach elite levels can raise injury risk if not built up progressively and carefully managed. In order to reap the health benefits of strong cardiovascular fitness, you have to sustain it. Short-term peaks that lead to breakdown don’t translate into long-term health gains.

Practical perspective: Sometimes, leaving a little untapped potential is the smarter trade-off. You can achieve enormous health benefits from developing a strong VO₂ max—even if not your absolute peak—while still preserving energy to invest in other qualities like skill, strength, power, etc.

Figure 2. Higher cardiorespiratory fitness is associated with lower mortality risk across all levels, with no upper limit to the benefit (Mandsager et al., 2018).

Taken together, these findings show that VO₂ max is one of the most powerful health markers we have. It outperforms traditional risk factors and delivers benefits at every level of fitness—from small improvements to elite performance—with no upper limit to the return.

Looking Forward

We’ve explored what VO₂ max is, why it matters for performance, and how research links it to long-term health. In the next post, we’ll shift from science to practice—breaking down how tactical athletes can train their VO₂ max in ways that build capacity without sacrificing durability.

The bottom line: developing a stronger aerobic engine is one of the most powerful tools a tactical athlete has to perform today and protect long-term health tomorrow. Even small improvements matter, and the strategies to achieve them are within reach.

References

- Kokkinos P, Faselis C, Samuel IBH, Lavie CJ, Sui X, Zhang J, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and mortality risk across the spectra of age, race, and sex. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(6):598-609. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.05.031

- Mandsager K, Harb S, Cremer P, Phelan D, Nissen SE, Jaber W. Association of cardiorespiratory fitness with long-term mortality among adults undergoing exercise treadmill testing. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183605. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3605