What Tactical Athletes Need to Know About Lactate

The Role of Lactate in Performance and Systemic Health

Introduction

In the last Tactical Vitality article, we explored VO₂ max — the ceiling of your aerobic capacity. VO₂ max represents how much oxygen your body can use during hard exercise, and it gives you a sense of your aerobic system’s maximum potential. But it doesn’t tell you how close to that limit you can sustain performance for long periods of time.

To understand sustained high-performance near our aerobic ceiling, we need to understand lactate. Lactate is not the “waste product” people used to think it was. It is a fuel your body produces at all times and a messenger that tells your cells how to adapt. It also forms the basis of lactate threshold, which is the exercise intensity where lactate begins to accumulate faster than it can be cleared — a key determinant of how long you can sustain hard work. Simply put, lactate matters for both health and performance, so it is important we understand it.

This article explores both sides of lactate:

- How the molecule itself supports health and adaptation, and

- How lactate threshold influences exercise performance

Lactate’s Systemic Influence

Lactate is produced any time your muscles break down carbohydrates for energy — which is all the time, even at rest. As exercise intensity rises, lactate production increases. But instead of being a useless byproduct, lactate is a portable energy source your body can quickly shuttle to where it’s needed.

Decades of research, led by George Brooks, shows that lactate moves between tissues to support energy production across the whole body.

Here’s what lactate actually does:

1. Lactate is a High-Quality Fuel

Your heart and brain both rely heavily on lactate during demanding efforts because it produces energy quickly. Many endurance-oriented muscle fibers also run efficiently on lactate, especially during sustained work. In practice, this means your body uses lactate as a readily available energy source for the heart, brain, and muscles—three of the foundational components for performance and longevity.

2. Lactate Helps Recycle Energy

Your liver can convert lactate back into usable glucose through a process called the Cori Cycle. This helps stabilize blood sugar during prolonged effort and prevents energy crashes when fuel becomes limited. This recycling loop allows you to keep working even when other energy sources start to run low.

3. Lactate Signals Your Body To Adapt

Lactate acts as a messenger that triggers several important training adaptations:

- The creation of new mitochondria (your cells’ energy factories)

- The growth of additional blood vessels

- The release of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), a molecule that supports brain health

These adaptations support improved endurance, cardiovascular function, and long-term brain health1. Now that we discussed what lactate is, let’s look at how it affects performance.

Lactate’s Role in Performance

While lactate influences many systems throughout the body, it’s most commonly discussed in the context of exercise performance, especially during high-intensity efforts. Lactate is always being produced—even at rest—but as exercise intensity increases, your muscles produce it at a faster rate. Eventually, you reach a point where lactate begins to rise faster than your body can clear it.

This point is known as lactate threshold, and once you cross it, fatigue accumulates quickly. After this threshold, your ability to sustain output drops sharply, which is why even well-trained athletes can hold efforts above threshold for only a few minutes. For an a relatively untrained endurance athlete, lactate threshold may occur as low as 55% of VO₂ max intensity, while for highly trained endurance athletes it may be as high at 85%2.

For tactical athletes, the implication is straightforward: the higher your lactate threshold, the harder you can work, and the longer you can sustain that work before fatiguing. This directly affects performance in any scenario requiring extended effort, repeated bursts, or sustained physical demand under stress.

Endurance performance is shaped by three major pillars:

- VO₂ max: the maximum capacity of your aerobic system

- Lactate threshold: the highest percentage of that capacity you can sustain for prolonged periods (30+ minutes)

- Movement economy: how much energy it costs to move at a given pace

We have previously explored strategies for improving VO₂ max, but lactate threshold represents a separate—and equally important—performance driver.

A Quick Note on Movement Economy

Although movement economy is one of the three pillars of endurance performance, I haven’t addressed it in depth yet because it deserves its own dedicated discussion. There is an extensive research base on biomechanics, running form, gait retraining, footwear, stride optimization, and neuromuscular coordination — all of which influence how much energy you expend at a given pace.

But for most tactical athletes, the key point is this: movement economy improves naturally through consistent, high-quality training. As you accumulate repetitions — whether through running, rucking, biking, or other endurance work — your body refines the movement pattern, builds resilience of the specific tissues involved in the movement, and becomes more metabolically efficient. While targeted drills and form coaching can help, the majority of improvements come simply from spending more time doing the activity itself. Over time, your system self-optimizes, reducing the “energetic cost” of movement and further supporting your ability to sustain higher outputs for longer durations. Improving movement economy lets you produce more speed with less energy cost, which directly raises your sustained performance capacity.

Lactate Threshold In Practice

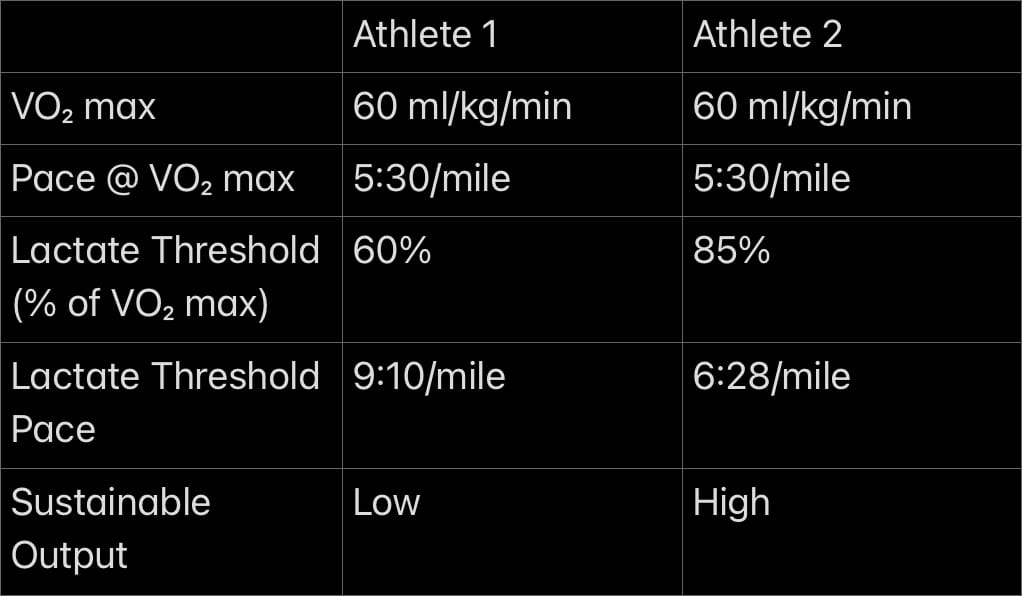

If lactate threshold is a new concept, it can be hard to appreciate how dramatically it affects performance. This side-by-side comparison helps make its impact clear. In this example, both athletes have the same VO₂ max of 60 ml/kg/min and can each run a maximal mile in 5 minutes and 30 seconds. Their engines are identical on paper.

Where they differ is in how much of that engine they can actually use. Athlete 1 reaches their lactate threshold at 60% of their VO₂ max, while Athlete 2 doesn’t hit threshold until 85%. The performance outcome is drastic: the second athlete can sustain a pace more than 2.5 minutes per mile faster before high levels of fatigue set in.

This difference has real consequences. The athlete with the higher lactate threshold has a far greater sustainable output — and in a tactical environment, the ability to maintain speed, power, and cognitive steadiness under fatigue directly influences mission effectiveness. Lactate threshold isn’t just a laboratory number; it meaningfully dictates how well you can perform when the environment is demanding.

How to Train to Improve Lactate Threshold

In a previous article, I emphasized the importance of training across a broad range of exercise intensities to maximize cardiorespiratory adaptation and reduce injury risk. Those principles still apply. However, improving lactate threshold requires a more targeted approach — one that exposes your body to intensities where lactate production and clearance are closely matched.

There are two primary ways to train lactate threshold, and both are effective for different reasons:

1. Threshold-Interval Training (Work + Short Rest)

This approach places you right at your lactate-threshold intensity, followed by a brief recovery period that allows partial lactate clearance, then repeats the effort. This structure lets you accumulate more total time at threshold without slipping into intensities that are too hard to sustain.

Why it works: Each interval elevates lactate, and each short rest brings it down just enough to maintain quality. Over time, your body becomes better at tolerating and clearing lactate, which raises the pace you can sustain before fatigue accelerates.

Example workout:

- 2–3 × 10 minutes at threshold pace or threshold heart rate

- 2–3 minutes easy between intervals

This should feel challenging but controlled — the fastest pace you can maintain without tipping into an all-out effort.

2. Continuous Threshold / Tempo Work (No Rest)

Threshold can also be trained through steady, continuous efforts slightly below, at, or just above threshold intensity. This is often referred to as “tempo work.”

Unlike interval-based threshold training, continuous tempo does not include rest. Instead, it keeps you in a sustained state where lactate rises gradually and your body must manage it over a longer duration.

Why it works: Continuous tempo efforts train durability near threshold — the ability to hold steady pressure, maintain form, and manage accumulated fatigue without backing off.

A simple example includes:

- 20–40 minutes of steady tempo running or rucking at or near lactate threshold pace/heart rate

This method is especially valuable for tactical athletes who need to maintain output over prolonged tasks rather than rely solely on repeated intervals.

How Lactate Threshold Is Measured

To train lactate threshold effectively, you need a reliable way to identify where your threshold occurs. Knowing both the workload (pace or power) and the heart rate associated with your lactate threshold allows you to target training intensity precisely and track improvements over time. There are three primary ways to determine this.

1. Laboratory Testing (Gold Standard)

This method uses a graded exercise test on a treadmill or bike, where intensity increases every few minutes. After each stage, a small blood sample is collected from the fingertip or ear to measure lactate concentration.

As intensity rises, lactate initially increases slowly before reaching a point where it begins rising rapidly — typically near 4 mmol/L, which corresponds to Lactate Threshold. Once this point is identified, the associated pace or power and heart rate are recorded and used to guide threshold training.

This is the most accurate and precise method for determining lactate threshold and provides the clearest data for training.

2. Field Testing

Field tests estimate lactate threshold without blood sampling. They are practical, accessible, and reliable when performed correctly.

Common field test – 30-minute time trial:

- Run or cycle as far as possible for 30 minutes.

- Build gradually over the first 10 minutes.

- Use the average pace/power and average heart rate from the final 20 minutes (minutes 10–30) as your estimated threshold values.

Because field tests rely on heart rate as an indirect indicator of lactate levels, accuracy matters. Optical wrist sensors can be inconsistent during intense effort, so using a chest strap is strongly recommended for the most reliable reading.

Other effective field methods include progressive run or ruck tests, as long as athletes judge intensity based on breathing, perceived exertion, and heart rate.

3. Wearables

Modern wearables estimate lactate threshold by analyzing heart rate data, pace or power output, and training history. Many devices now include guided threshold tests, which function similarly to structured field tests.

While wearables are not as precise as laboratory testing, they are useful for:

- Identifying general threshold zones

- Tracking changes over time

- Providing accessible, repeated assessments

When using wearable-guided tests, the same principles apply: rely on consistent pacing, controlled effort, and, whenever possible, a chest-strap heart rate monitor for better accuracy.

Conclusion

Lactate fuels your brain and heart, drives mitochondrial growth, supports healthy blood sugar regulation, and helps your body adapt to training. Your lactate threshold — the point where lactate production exceeds clearance — ultimately determines how much sustainable work you can perform. Together, these roles make lactate one of the most important molecules in tactical performance. Training in a way that improves lactate threshold strengthens both your operational capability and your long-term systemic health.

References

- Brooks GA. The science and translation of lactate shuttle theory. Cell Metab. 2018;27(4):757-785. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.008.

- MacDougall JD, Sale DG. The Physiology of Training for High Performance. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014:31.