Developing VO₂ Max for Tactical Athletes

How to Build Your Aerobic System for Sustainable Performance

Introduction

Tactical athletes face unpredictable demands—long marches, heavy lifts, sprints under load, and everything in between. Fitness can’t be one-dimensional. In dynamic, high-stress environments, aerobic fitness isn’t optional—it’s foundational. It underpins the ability to cover distance, sustain strength, power, and skill under fatigue, and recover quickly enough to perform again. By delaying the onset of exhaustion, it keeps these qualities available when they’re needed most.

VO₂ max is the gold standard for quantifying aerobic fitness. It reflects how much oxygen your body can deliver and use when exercise intensity is highest. Think of it as your aerobic ceiling: the higher it is, the more sustainable work you can perform, the faster you can recover, and the more resilient you’ll be under stress. For tactical athletes, where performance under stress often determines mission success, that ceiling is critical.

This post will cover what drives VO₂ max, how to train it, and how to balance gains with durability—highlighting key considerations for tactical athletes.

What Determines VO₂ Max?

VO₂ max comes down to two things: how much oxygen-rich blood your heart can deliver and how well your muscles can use it. The Fick equation makes this clear:

VO₂ = Cardiac Output × Oxygen Extraction—in plain terms, how much blood your heart can pump × how much oxygen your muscles can actually use.

The factors that matter most for improving VO₂ max come straight from the Fick equation. Exercise drives the physiological adaptations that raise VO₂ max, and these fall into two broad categories:

- Central Adaptations (heart and blood): The primary drivers are increases in stroke volume (how much blood the heart pumps with each beat) and total blood volume (how much oxygen-rich blood circulates in the body). These changes respond best to longer training sessions (rather than hard ones), though intensity still matters. These adaptations take months to develop but also take longer to fade if training stops.

- Peripheral Adaptations (muscles): The key factors are increased capillarization (growth of tiny blood vessels in working muscles) and improvements within the muscle itself—especially in mitochondria (the cell’s power plants) and oxidative enzymes (the tools that turn oxygen into usable energy). These adaptations allow muscles to extract more oxygen from the blood and convert it into performance. They respond most to higher-intensity training and can develop within weeks. The tradeoff: they also fade quickly if training stops.¹

To maximize VO₂ max, you can’t rely on just one side of the equation. It doesn’t matter how well your muscles can extract oxygen if your heart isn’t delivering enough blood. And it doesn’t matter how much blood your heart can pump if your muscles can’t use it. Tactical athletes need both—built through exercising with the right balance of duration and intensity over time.

Measuring Training Intensity

To get the most out of VO₂ max training, you need a reliable way to keep your effort in the right range. Exercise zones are a straightforward and practical tool for doing exactly that. Some athletes prefer to measure intensity with heart rate, while others go by feel. Both are valid approaches, and the example below shows how training zones can help guide intensity:

If you use heart rate to guide intensity, you’ll need an estimate of your maximum heart rate (HRmax) so you can calculate percentages. A quick formula is:

HRmax = 220-age

This estimate isn’t perfect, but it’s good enough to get started and produces solid results. For greater precision, a maximal effort exercise test with a chest strap monitor is needed to determine your exact HRmax.

Note: Training zones aren’t universal. Different systems define them slightly differently, but the purpose is the same: to align your effort with the intended goal of the workout. What matters most is consistency — using the same framework to measure, track, and adjust your training over time.

How to Train VO₂ Max

To raise VO₂ max, you need to train across the full spectrum of exercise intensity. Different intensities create different adaptations, and you need all of them to maximize results. Training at the right intensities at an appropriate volume is what allows you to make sustainable progress over time.

Below is a breakdown of the main training zones, their purpose, and the approximate share of your weekly endurance training volume they should represent.

Zone 1 – Recovery

- Weekly Volume: <5%

- Effort: Very light movement (<60% HRmax).

- Purpose: Increases bloodflow and facilitates recovery from harder sessions, but does not meaningfully improve VO₂ max.

- Key Point: Treat this as recovery—not programmed training.

Zone 2 – Aerobic Base

- Weekly Volume: ~75–80%

- Effort: Long, steady sessions (30–45+ minutes) at 60–70% HRmax.

- Purpose: Drives central adaptations (increased stroke volume and blood volume). Builds aerobic efficiency and conditions tissues to tolerate higher intensity exercise.

- Key Point: The cornerstone of VO₂ max training. Most of your endurance work belongs here.

Zone 3 – Endurance Capacity

- Weekly Volume: ~10–15%

- Effort: Sustained work at 70–80% HRmax.

- Purpose: Improves endurance capacity and also contributes to central adaptations. More fatiguing than Zone 2, so it should be used intentionally.

- Key Point: It bridges the gap between base training and high-intensity intervals.

Zones 4–5 – Maximal Capacity

- Weekly Volume: ~10%

- Effort: Short intervals at 85–100% HRmax, performed near max effort.

- Purpose: Stimulates peripheral adaptations (increased muscle capillaries, mitochondrial density, oxidative enzymes). Raises the ceiling of aerobic performance.

- Key Point: Powerful but fatiguing. Use selectively to avoid overtraining and injury.

This layered approach is effective because each zone supports the next: Zone 2 builds the base, Zone 3 adds capacity, and Zones 4–5 raise the ceiling. Zone 1, meanwhile, exists mainly for recovery.

Keep in mind: these are general guidelines, not hard rules. Everyone has different goals, training histories, and recovery needs. The framework above works well for most athletes, but the exact mix should be adapted to your individual context.

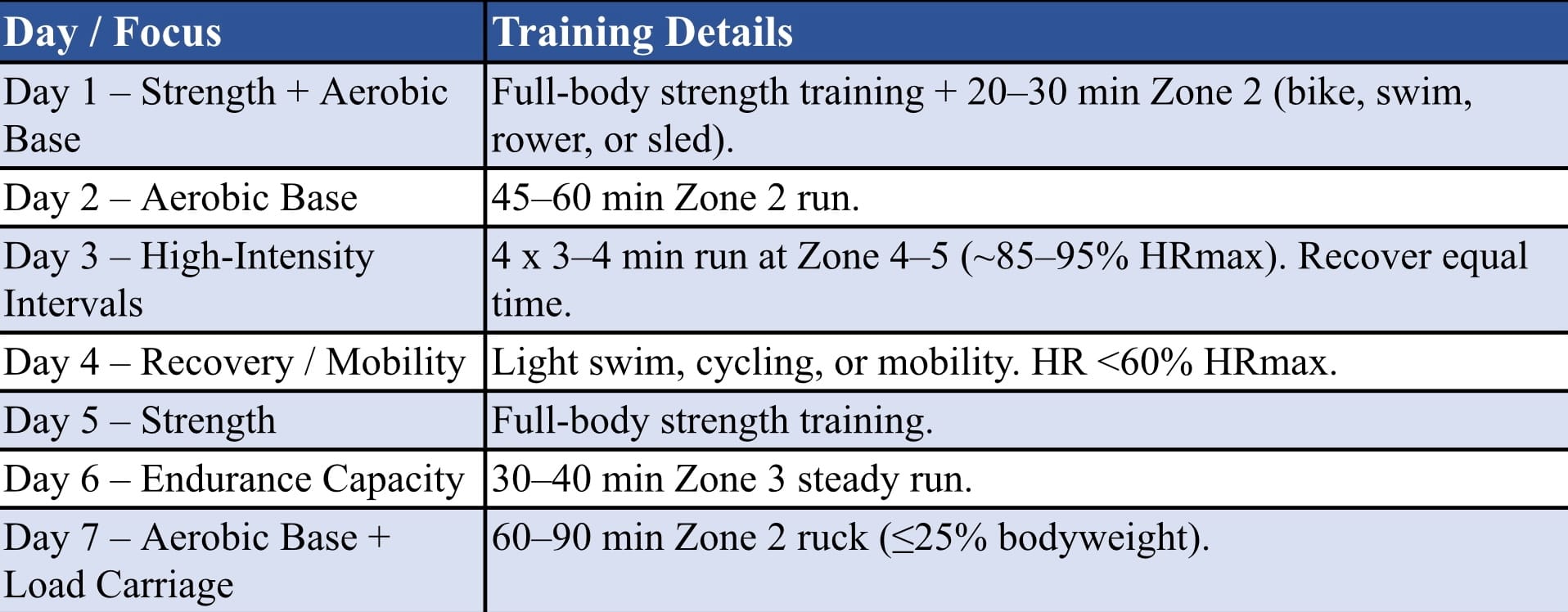

Sample Training Week

A VO₂ max–focused week for a tactical athlete should balance aerobic base work, high-intensity intervals, strength, and occasional load carriage—while still leaving room for recovery. Using a variety of modalities (running, rucking, cycling, rowing, swimming, etc.) reduces stress and builds versatility. Here’s one example of how that balance might look:

This template isn’t a rigid prescription—it’s an example of how to program VO₂ max development in a way that sustainably improves performance. Your exact plan will depend on your goals, background, and operational demands. What matters is the principle: build a strong aerobic base, sharpen it with selective intensity, reinforce it with strength, and protect it with recovery.

This sample week also assumes a fairly high level of aerobic fitness—and tolerance for running and rucking—from the start. For those less trained, the total volume will likely be too much and should be scaled back. Adjust to your current capacity and progress gradually. Trying to jump straight into this structure without building up first is a fast track to injury.

Finally, the plan includes two full-body strength sessions per week, but with limited detail. That’s intentional. It’s not the only way to program strength training, but it’s one effective option. Since the main focus here is VO₂ max, strength training specifics will be covered more in future posts.

After seeing how training zones fit together in practice, it’s worth zooming in on one that gets the most attention in endurance circles—Zone 2.

Zone 2 Training Explained

Zone 2 training has become a buzzword in the fitness world recently. While it’s not the only type of training you should do, it is one of the most powerful tools for building aerobic fitness. For most people, Zone 2 should make up the majority of aerobic training.

Practical definition: Exercise intensity you can sustain almost indefinitely. You can hold a conversation, but it feels slightly strained.

Scientific definition: The highest intensity of aerobic exercise you can maintain while blood lactate stays below ~2 millimoles per liter (mmol/L). In this range, nearly all energy production is aerobic. Push harder, and lactate begins to accumulate faster than your body can clear it—leading to fatigue.

Note: “Zone 2” is a commonly used term, but definitions of training zones vary. Most often, it refers to steady, primarily aerobic work just below the threshold where fatigue begins to build.

Benefits of Zone 2 Training

- Builds the aerobic foundation on which higher-intensity work can be layered.

- Conditions tissues to tolerate sustained load, improving durability.

- Is highly recoverable, allowing frequent training without excessive fatigue.

Drawbacks

- Because it feels “easy,” the stimulus can seem underwhelming. Meaningful gains usually require 30–45 minutes or more.

- On its own, Zone 2 won’t maximize VO₂ max or high-intensity tolerance. Without complementary higher-intensity work, you’ll lack the ceiling to perform at your best.

Bottom line: Zone 2 is the foundation of aerobic fitness. It builds the base that higher-intensity training adds on top of.

A Note on Longevity

Zone 2 training is often highlighted for its role in healthy aging. One reason is its close connection to mitochondrial health—the tiny “power plants” of your cells that convert oxygen and fuel into usable energy. Because mitochondrial function declines with age, training at an intensity that relies heavily on the mitochondria may help preserve it and reduce disease risk.

Zone 2 training has developed a strong following in recent years, with some treating it as the ultimate key to health and performance. While it is undeniably valuable, viewing it as “magical” overlooks the importance of training across a spectrum of intensities. The stronger takeaway is this: aerobic fitness as a whole is one of the most powerful predictors of lifespan. Research consistently shows that VO₂ max is closely tied to mortality risk—a connection I examined in my previous article.

Physician Peter Attia, one of the leading advocates for Zone 2, frames it primarily through this lens of longevity. His work underscores how training at this level can extend healthspan, while also reinforcing its value for performance. For readers who want to explore this further, his book Outlive is an excellent resource.2

Orthopedic Considerations

As a physical therapist working with tactical athletes daily, I see far more injuries caused by overuse than by trauma. Most of the pain people associate with training—shin splints, stress fractures, tendinopathies, plantar fasciitis, knee pain—comes down to a simple mismatch: Training volume exceeds the capacity of the tissues to tolerate it. When stress outweighs capacity, pain and injury follow.

The key to durability isn’t avoiding stress altogether—it’s applying an appropriate dose, with an appropriate progression. Training intentionally not only reduces injury risk but ensures athletes can keep training consistently. And consistency is what drives performance. If you’re sidelined with injury, you can’t train. And if you can’t train, you can’t improve. Here’s what keeps tactical athletes durable while building aerobic capacity:

- Progress Appropriately – A simple rule of thumb is to increase training volume (time, distance, speed) by no more than 10–15% per week. Pushing past this threshold too quickly is one of the most common drivers of overuse injuries.

- Use a Variety of Modalities – Aerobic fitness isn’t limited to one form of exercise. Repeating the same movement pattern—especially running or rucking—over and over increases risk of overuse pain. Mixing in cycling, rowing, sled work, incline treadmill waking, etc. distributes stress across tissues while still driving aerobic gains.

- Apply the 80/20 Rule – Keep ~80% of training easy and save ~20% for 1–2 hard sessions per week. This balance makes most training highly recoverable while still seletively applying the high-intensity stress needed to adapt.

- Strength Training is Non-Negotiable – Strength training improves tissue capacity, enhances movement efficiency, and builds resilience against impact. For endurance athletes who want sustainable performance, strength training is essential.

Bottom line: Durability isn’t about training harder; it’s about training smarter. With the right mix of progression, variety, balance, and strength training, you can keep improving while staying injury-free.

Tactical Athlete Considerations

While the orthopedic principles above apply to anyone training for endurance, tactical athletes face unique demands. Their training needs to prepare them for domain-specific performance while minimizing injury risk from job-related tasks.

Load Carriage (Rucking) Must Be Programmed Intentionally

Rucking is unavoidable for most tactical athletes. It’s often labeled “bad for your joints,” but no activity is inherently good or bad—it depends on how it’s programmed. Like any stress, the demand has to match your tissue tolerance, or pain will follow.

As a general guideline, keep ruck weight at or below ~25% of bodyweight most of the time unless you’re preparing for a specific event that requires more. Heavier loads can be used occasionally but shouldn’t become the norm. For most athletes, rucking every 7–14 days strikes the right balance: frequent enough to maintain tolerance, but not so much that it drives overuse injuries.

Finally, if you’re new to rucking—or returning after time off—start with lighter weight and shorter distances, then progress gradually. Just like strength training, the key is progressive overload, not jumping straight to heavy loads.

Weight-Bearing Aerobic Work Is Necessary

Non-weight-bearing cardio (cycling, rowing, swimming) is excellent for the heart and a valuable tool for recovery and variety. But tactical athletes must also be ready for prolonged, weight-bearing movement—sometimes under load. Running, incline treadmill walking, sled work, rucking, etc. should form the backbone of training. Low-impact modalities can and should be rotated in to reduce repetitive stress, but ideally they shouldn’t replace weight-bearing conditioning as the primary mode. Otherwise, your tissues won‘t be ready for the demands of your job.

Train for the Unknown

Variety in training reduces overuse injuries — but for tactical athletes, it also develops range. The unpredictable nature of the job means that the broader your preparation, the better you can respond to uncertainty. Incorporate a wide range of modalities into your program to develop versatility.

That said, if you have a specific performance goal (for example, running 5 miles in under 40 minutes), your training should emphasize that modality. You’ll always see the best results when your training is specific to the outcome you want. The trade-off is that the more narrowly you train, the greater your risk of overuse injuries. Every training decision carries pros and cons — the key is aligning your approach with both your goals and your long-term durability.

The Bottom Line

VO₂ max is your aerobic ceiling. The higher it is, the more work you can sustain, the faster you recover, and the more resilient you are under stress.

Key Points:

- Build a strong aerobic base with Zone 2 training — this should make up the majority of your training volume.

- Raise your ceiling by strategically incorporating high-intensity intervals.

- Progress gradually and mix modalities to protect tissues.

- Reinforce durability with consistent strength training.

Quick Note:

This article focused on VO₂ max as your aerobic ceiling — critical for both performance and longevity. But equally important for performance is the percentage of that ceiling you can sustain without fatiguing, which is largely determined by your lactate threshold. We didn’t cover that here, but it’s a key piece of the puzzle. After wrapping up this VO₂ max series, we’ll take a deeper dive into lactate threshold and its role in tactical performance.

Looking Forward

Next, we’ll cover how to test your VO₂ max, what your score actually says about your fitness, and how much improvement you can realistically expect with training.

References

- MacDougall JD, Sale DG. The Physiology of Training for High Performance. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014:79-83.

- Attia P, Gifford B. Outlive: The Science & Art of Longevity. New York: Harmony Books; 2023:237-244.